|

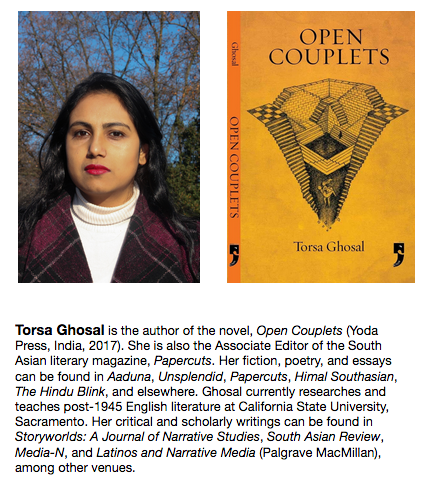

Excerpt from Open Couplets (Yoda Press, India, 2017)

Ira, in the ruins of one world, another finds its spark. That is the two-century old bond tethering Delhi to Lucknow. Journeying from Delhi to Lucknow today is like walking between two parallel mirrors. My language and my story are trapped in this route, eternally recurring in reverse. Each recurrence diminishes its scope and compromises its stature. It is curious how, even before I knew anything about Lucknow’s history in any formal sense, I lived with the

anxiety that this city might flicker out of existence as though it were a reflection of some other time and place. Your mother’s Lucknow is a stable city. It is stable even in its decadence. My Lucknow shrinks and expands overnight, contingent on the slope of light, on the turn of season. This flickering premise, I kept convincing myself, can solely endure in language, as Urdu.

… Before Ghalib’s letters and poems decried the demise of Urdu with the destruction of old Delhi’s markets, forts, and lanes, Meer, the ustad who even the pompous Ghalib swore by, had been forced out of that city’s courts. Sitting in Urdu classes, I would see Meer enter the streets of Lucknow clad in a plain angrakha and qalpaq. Now Meer is a poet-genius, the court ought to revere him for his simplicity. He throws in a richly decorated but worn out katzeb, spun out of cotton with wide silk borders, just because. This is the Meer, celebrity poet of the Delhi Durbar, the ladies’ man. The Meer who would but die for each woman he has loved and there are many. Our poet is no alien to journeys. After all, Shahjahanabad was only his adopted address. But what does he find in Lucknow? A crass durbar that is worse than the ruins of Shahjahanabad. His Lakhnavi colleagues at Asaf-ud- Daulah’s do not share his vocabulary, taste, or humor. Instead of learning a thing or two from the sire of Urdu poetry, they laugh at him. Feelings of dislike and distrust are mutual. To Meer, the mushairas in Lucknow’s Chowk are a joke. No sophisticated repartee exchanged among court poets, sipping wine while sitting on ornate diwans. Straight fights. Cocks, kites, and poets fight not only within walled compounds but also on the streets. And there are those audacious low-caste women who discuss cocks of the other kind and giggle in their zubaan. The drawstrings here are loose and if you love, you don’t die but laugh. No wonder that Insha, who did not find takers in Delhi, finds patrons here. That ustad of the profane does not know the first thing about the melancholic cravings of mashooq. He fools around, using an effeminate pseudonym, weaving dastaans eulogizing the battle of bangles and the knotty sisters. Thankfully, Lucknow turns out to be a great leveler in the end. Both Meer and Insha die poor, bereft of patronage.

Meanwhile, Asaf-ud- Daulah himself spends time with Claude Martin, running elaborate copy and paste programs: lift ideas of minarets, gateways, and domes from Delhi and Turkey and plant those in Lucknow. Lucknow a la Las Vegas before Las Vegas. While a soldier in the French army, Martin started dreaming of expansive marble mansions. Lucknow lacks the stuff to materialize his dreams. Not to worry. With the nawab’s blessings, Martin sets about replicating in brick what he fancies in marble. When the Nawab and his architect take breaks from building the massive collage that is Lucknow, they too enter cock fights with high stakes. Meer’s ghazals can only fall on deaf ears there. His jinxed rapport with Lucknow continues centuries after his death. I hear that his grave has disappeared now. Perhaps they did not dig it deep enough.

|