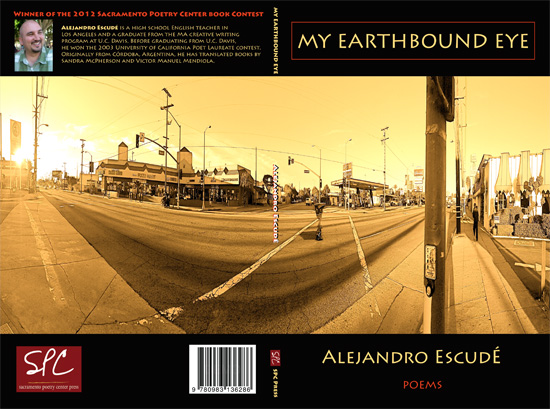

Alejandro Escudé

Alejandro Escudé’s My Earthbound Eye is the 2012 Sacramento Poetry Center Press Book Manuscript Award winner.

Alejandro Escudé is a high school English teacher in Los Angeles and a graduate from the MA creative writing program at U.C. Davis. Before graduating from U.C. Davis, he won the 2003 University of California Poet Laureate contest. Originally from Córdoba, Argentina, he has translated books by Sandra McPherson and Victor Manuel Mendiola.

Praise for My Earthbound Eye:

In the remarkable sonnet sequence that opens this book, Alejandro Escudé recalls his childhood emigration from Córdoba, Argentina to Los Angeles, to a world where nothing belongs to him: his parents build and clean other people’s houses and, at first, he can barely speak English. “An immigrant’s unsolvable question,” he reveals, is “Do I belong to this?”—this culture, this landscape, this new world. Most of these poems grapple with the question of belonging as the poet stands in and outside his various roles as son, husband, father, teacher, poet. The poems answer the immigrant’s question both yes and no. On the one hand, their speakers are profoundly embedded in the communities of family, work, and art, while at the same time they mistrust even the closet interpersonal relationships: “My life hasn’t been lived for others.” Even if he is loathe to admit it, the poet’s ultimate allegiance is not to Argentina, America, or Spain, but to what the title of one poem calls “The Country of Poetry.” Despite the presence of parents, wife, and children in many of these poems, the book ends with our hero alone at a museum, communing with Picasso and Calder and thinking of Lorca in a stolen moment before the doors officially open. Afterwards he sits by himself “at one of the café tables / and watch[es] the multitudes queue.” You, too, will want to settle down at a café for the afternoon—the first of many—to pore over, imbibe, and enjoy Escudé’s poems with their magnificently unsolvable questions. — Eric Gudas

Alejandro Escudé’s My Earthbound Eye stares into the eye of the everyday world, the world where we all live – the world of work, love, marriage, fatherhood, of memory and loss – and does not blink. From the initial sequence ‘The immigrant’s Question’, detailing his family’s journey from Argentina to Los Angeles, to the poems that fearlessly shine a light on the many trepidations and struggles of family life, he is always searching, asking questions, trying to wring some kind of truth from the mystery of it all. What does it mean to be a man? What does it mean to be a father, a husband, a son? What is this world we live in? What does it mean to just BE? But there is no transcendental yearning going on here, he is asking his questions from what is right there in front of him: The death of a neighbour; a conversation overheard in a market; standing in front of a class of teenagers, asked to define ‘solitude’; both kids crying at 2am… Funny, angry, dark, these grounded poems show that what we do, how we struggle, day after day, is poetry – if we can only see with Escudé’s ‘earthbound eye’. — Christien Gholson

From My Earthbound Eye:

Miedo a Nada

I’ve become enamored with my hands.

They are soft

And muscular; I break them and they come back,

Only slower. I watch them

Correct student papers, and they’re as assured

As ever, more assured than

My soul even, who still ponders,

Fears for its existence.

When I fret about something

My hands gaze at me

Like two loving dogs.

Then they go about the business

Of doing.

My hands know about the brain,

But they only

Nod to it, then do what it orders them to do.

Like soldiers, they don’t question,

Though they have their own feelings

Their own opinions.

My hands are bronze—Argentinian

Like Mother

Who taught me only last week

The phrase miedo a nada, fear nothing,

As she and I strolled

The beachside park

Along the yachts of Marina Del Rey.

It wasn’t advice

Only a way to punctuate,

Miedo a nada, fear nothing,

A point I was stressing about difficult family,

Coworkers, students, friends…

She didn’t say it, miedo a nada,

Like a mother would,

But more as an old confidante,

She didn’t say it

In her hurried breath, as she might have

When I, a rag and a bottle

Of Pledge in my young hands,

Watched her, propel someone else’s

Soaked mop, empty their vacuum,

So many years, turning her face

To cough up the dust.

Miedo a nada

The two of us just

Strolling, strolling

Miedo a nada

Along those beautiful yachts,

Mahogany handrails, crisp white

Sails, one perhaps even owned

By people she worked for.

Miedo a nada

Then, we walked in quiet

Side by side

Long enough

For me to realize Mother and I

Miedo a nada

Were walking side by side.

Pause

As if the sun were never to rise again, it makes sense

to crush my son, a human tadpole.

Dreadful desire,

stomping him in that nightmare as one would a spider.

From behind my pillow, the crisp fall desert air.

Getting there, always getting there.

Electric poles, wires like nerves. Tobacco scent,

Father’s wet hand fixing another toilet, the death

of both my uncles,

my high school girlfriend’s voice

on the line over a driveway in Compton, fried rice

wafting from the corner Chinese restaurant a long

block away, where the signal pauses, continues on.

You can also order here:

Sacramento Poetry Center

1719 25th Street

Sacramento, CA 95816

ISBN-13: 978-0-9831362-8-6or for other arrangements, e-mail Sacramento Poetry Center Press

or call 916-714-5401