The poetry legions arrived at 25th Street hungry for poems by Kathleen Lynch but not much else as the luscious spread that was provided for the event went virtually untouched (except for the strawberries . . . why is it that they always go first from the fruit tray while the blocks of melon must suffer the fate of the neglected? Is the attraction to the red a reminder of blood, a repressed memory of a communion that champions the cause of minimal calorie intake?)

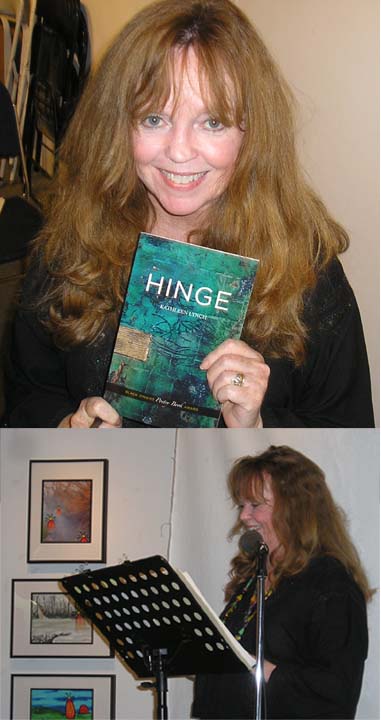

Kathleen Lynch started off the evening giving thanks to all, including Gloria Sanchez Jackson who designed the stunning cover for her book as well as the beaded necklace that Lynch wore. Then Lynch passed a broadside of “Apricot Tree,” which had come about as a result of Susan Kelly-Dewitt’s efforts to produce a broadside of the poem in the past. All those in attendance received one of the broadsides (see what treasures you miss when you stay home, Sacramento).

Lynch explained how Hinge was organized in terms of “arrival” and “departure”, a “getting here” and “leaving.” Before one has arrived, one must look at family photographs for some insight into the conditions of arrival. Lynch first read “Hanging Family Photographs” where she informs, “Always when an outside thing rages, an inside thing sifts information, and a voice within says Forget what you wish for. Get up and go. Now.” With this advice, Lynch was graciously giving her listeners one last opportunity to leave, but no one departed. She was off and running, just like her poem had commanded.

The opening poem in the book, “How I Got Here” recounts Lynch’s pre-life as a bird remembering what it was like to arrive in this actual world. The speaker, after soaring over roads, valleys and rivers, chooses a house, folds its wings and dives in.

“Linoleum,” a poem not found in Hinge was the next poem on the docket. It featured a little girl’s voice as the subject. In the opening tableaux she appears in shoes that are described as having the color of oxblood. She is drawing pictures, stick figures of three daughters, herself in the middle in a yellow dress, the two others, flanking, in blue. The scene switches to the kitchen where the father is listening to trusted newsman Gabriel Heater deliver news about the Korean War. The little girl speaker sees a mockingbird and wishes she knew bird talk. She is conjuring her wonder about the unseen world when she asks how far away Korea is and whther they have to kill the ox to get that color on her shoes.

“Canned Food Drive” was another poem that was taken out from Hingeat the last moment and inserted into another publication. the poem also has to do with the “war years.” The speaker, reminiscing, remembers the planes roaring over McClellan AFB, how the planes rattled the windows, pounding, one great heart as if it were ours.

At this point Lynch welcomed two newbies to the poetry scene who were attending their first poetry event in Sacramento [Yes, Sacramentans, there is always a first time, and you never forget it . . . you want to measure all successive poetry readings by that initial mark.]. Those two were Chelsea Fink and Jenny [undisclosed name]. Then the initiation moved on.

Before “Chicken in the Snow” Lynch told the story of how her grandson Elliot liked this particular poem (“probably because of the gore” she mused) and how Elliot had given her advice during the reading in Walnut Creek where she had read this poem for the first time. Elliot had told her, (read them) “One at a time, grandma, one at a time.” The poem is a recollection of a childhood trip to Kyburz, the little mountain town off of US 50, for a family holiday feast. The star of the ceremony was a chicken that had ridden in a cage all the way up from Sacramento. The speaker starts to empathize with the doomed creature, and when the head comes off, the result is downplayed by the lure of something magical. The event leads the speaker to two thoughts, one about the dead and the other about the misfortunate.

“Love: The Basics” is the poem that kicks off the first section of the book. It invokes a litany of inanimate objects that should be loved. The speaker reveals how and why but cautions the reader not to expect too much.

“Observation” was dedicated to Eddie, Lynch’s birdwatching husband. Lynch observed that the patience and careful attention that is required for birdwatching and other “scientific” efforts make a good model for writing poems. “Observation” is a “fixed-frame” poem that closely watches a peregrine falcon kill and eat a smaller bird. The insight at the end of the poem is that there is redemption for the dead bird, that it has not been physically subjugated by the more powerful bird as much as it has entered into a relationship with the falcon, a more parallel relationship.

In “Vocation” the speaker imagines an alternative life as a nun (Lynch intimated that this had been a real option for her when she was younger), apart from more worldly sorrows and pleasures. The result would have likely been the same: longing for an ultimately other kind of existence.

Lynch was not going to read “Apricot Tree” because she thought those in attendance could do that at our own leisure ( a little homework from Lynch?), but she was strong-armed into reading it by certain members of the audience who foisted their desire for it to be read onto Lynch. Lynch complied like the “good little girl” she once may have been before she turned “tacky”. “Apricot Tree” reveals a small girl reading a book in a tree. The world transpires below her while she encroaches on the “orange worlds” she is reading about. Finally, the sky intones for her not to move from her sanctified position in the tree. It tells her to “Hold Green. Hold Dark.”

Lynch disclosed that “Boys at Play: Armando Remembers” was derived from a dream she had about being a Hispanic boy bent on acknowledging his desire to separate from the manly expectations placed on him and pursue more feminine pleasures. the poem begins with the scene of a bunch of boys who are “matadors on bicycles.” The final line of the poem suggests some foreboding for this feminized Hispanic boy and Lynch remarked that that line occurred to her before some of the actual violence that has been documented locally occurred.

“The Spirit of Things” was written after Morris Graves, American abstract expressionist painter, and in the poem the speaker imagines the sacrifices Graves made by never having a family. The poem presents a surreal episode where a childless speaker carries four stones to a restaurant, orders food for all of them and then has a flash of insight about who escapes responsibility and who does not.

“The Hard Season,” another poem not found in the book, was dedicated to all those who had recently or not-so-recently experienced a downturn in their luck. It is a poem about how one must essentially welcome those things that are unwanted, like rain against a retaining wall, like mice who visit a home (my own problem is with ants, the little buggers). The final wisdom revealed is for one to trust his/her persistence.

Lynch spoke of how an aristocratic friend had come to visit her and despite his accomplishment and brilliance, he began to grate as a visitor. “Handmaiden’s Lament” was dedicated to the traveling season when many from out-of-state find themselves on the doorsteps of their California friends. The poem used the diction and formal speech of a nineteenth century servant to pierce the assumptions made by those who are served.

The big feel-good hit of the night was “Soap Fans,” where Lynch took her audience through a litany of improbabilities and absurdities that the soaps employ and subjects them to some consideration. In the end, the speaker, recovering from a deep coma where she has had many visitors, threatens to “tell everything I know.”

A nameless audience member implored Lynch for an encore. Lynch, ever gracious, complied against her will. She searched the book for an upbeat follow-up to “Soap Fans” and settled on the poem “Drifters.” She apologized for not taking us out on a chipper note. The poem recounts an incident where the speaker became lost in Nogales after making a wrong turn. While briefly attributing this to the disorienting music (Monk’s Driftin’ on a Reed that was playing on the radio, the speaker encounters a band of aggressive window washers south of the border. The poem chronicles the moral dilemma of the situation and the dim hope of being able to remove oneself from the world of mistakes.

Everything was wrapped up, and Lynch made one more plea for attendees to stuff themselves, but the fear of obesity runs deep in these American poets. I thought I heard a chunk of melon call my name. You might have too if you’d been there . . . and listening.