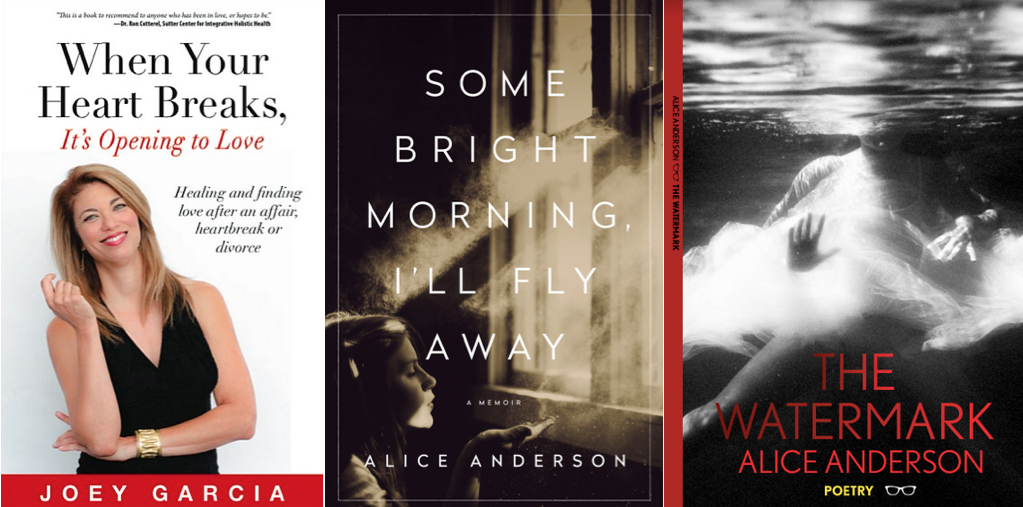

Joey Garcia is a co-founder of the first-ever Belize Writers’ Conference (scheduled for April 2018). She was born in Belize, raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, and now lives in Sac with a big dog and a small cat. Joey’s memoir was a 2017 San Francisco Writers Conference nonfiction finalist. She has received a 2014 Pushcart nomination (poetry); 1996 Isadore Paiewonsky Poetry Prize; 1996 Spoleto Writers Fellowship (poetry); 1995 Paris Writers Fellowship (poetry); 1995 Randall Jarrell International Poetry Prize, honorable mention (selected by Lucille Clifton), 1995 Soul-making Spiritual Autobiography Prize, third place; among others. She has been published in Calyx; The Caribbean Writer; Presence Journal; Tule Review; Poetry Now; The Farallon Review, and several anthologies including Bedside Prayers, and New to North America: Immigrants their children and grandchildren. She has been a featured reader at Shakespeare & Company in Paris, LitCrawl in San Francisco and at the Sacramento Poetry Center. For over 20 years, Joey has written a relationship advice column for the Sacramento News & Review newspaper. She is also the Relationship Expert for Fox 40 News. Her award-winning book, “When Your Heart Breaks, It’s Opening to Love,” is available on Amazon and at select Barnes & Noble and indie bookstores. Joey is at work on a novel about a young Belizean-American reporter with PTSD who is on the crime beat for a California radio station.

The Lemon Cure

At Esposito’s Nursery we wander

through aisles of our new landscape,

searching for a recuerdo, some way

to remember Belize. My father

dismisses a solicitous blonde clerk,

twice. She smiles, excavating

a sidewalk of teeth. He buries

gold-framed front teeth behind

immigrant-tight lips and bends

slowly to re-tie my shoelace, until

she walks away. Afterwards

more aisles of the unfamiliar:

no gumbolindo, no strong-u- back,

no ceiba, soursap, basket tie tie,

no jackass bitters or hog plum,

no bullet trees or papaya.

Instead a familiar sound—

English grafted to the snapping twigs

and bursting vowels of a foreign accent.

We hurry toward that hybrid

as the gravel under our feet

sings in its own broken voice.

A man with eyes as skinny as mango leaves,

points us, as requested, toward lemon trees,

each no taller than a duende. My father polishes

the satin between a thumb and forefinger as he

perfumes the air with tales of the gordo lemons

he grew in Belize. He questions the man about

care in this climate. The answers are simple,

unsmiling. Satisfied, we buy.

A month passes and the tree blooms

small creamy flowers that smell

like the evening breeze in Corozal.

My father visits the tree after work

each night, seeding me and those blossoms

with stories from Belize of all the ways

a lemon can cure. Three lemons swell

on the still short tree. We expected

more, but one hot Saturday

we harvest, intending lemonade.

My father slices the fruit into crowns,

and squeezes above a plastic pitcher

sweating with water, ice and cane sugar.

The lemon dribbles. Four seeds blurt

into a teaspoon of juice. We try the juicer

but each lemon refuses expression.

With a leaf and Saran-wrapped lemon,

we return to Esposito’s and find

the skinny-eyed man. He listens,

rolling the split fruit

between soil-pocked hands.

You buy this, he says.

I already bought that, says my father.

Yes, the man says, bowing a little.

My father sours. I run for help,

returning with the blonde.

She apologizes: “This employee

is new to North America. His English

isn’t good. These trees are dwarves

bearing fruit for decoration, not eating.”

She offers my father a refund.

He declines with a gold-toothed grin.

Walking to our car he says:

“Add fear of being an immigrant

and making mistakes

to the ailments a lemon cures.”

—Joey Garcia

Alice Anderson is the author of The Watermark, published in the UK and US simultaneously from Eyewear Publishing, and Human Nature: Poems, awarded both the Best First Book Prize from the Great Lakes Colleges Association and the Elmer Holmes Bobst Prize from NYU. About Human Nature, Cheryl Strayed said: “Alice Anderson’s honesty will take your breath away. She has the courage to tell her heart’s deepest, darkest truths while never compromising on the poet’s craft. Anderson’s poems are rigorous and right. Human Nature is an amazing book.” Anderson’s memoir, Some Bright Morning I’ll Fly Away, is forthcoming August 29, 2017 from St. Martin’s Press. Lidia Yuknavitch said: “Alice Anderson’s Some Bright Morning I’ll Fly Away is nothing short of a body and soul retrieval.” With work appearing in journals such as New Letters, CUTTHROAT, The New York Quarterly, Tupelo Quarterly, and AGNI, Anderson is anthologized in On The Verge: Emerging Poets and Artists in America; American Poetry, The Next Generation. She is at work on a third poetry collection and a novel.

THE SPLIT

This is how it happens. You are just out of the shower maybe

in the afternoon when your lover comes up behind you and kisses you

on the shoulder. You turn, kiss back. And you even remind yourself,

during that first heavy breath or fall to the bed I am not

going to close my eyes. But you cannot help yourself and you

close your eyes, forgetting your promise, and you see him.

A figure, moving form, enormous shadow appearing somewhere

between your eyelids and the air. There he is above you

and for a moment you are happy about it, amazed to feel again

what it is to be that small. How exquisite your tiny fingers,

how fragile the bones of your wrists. You see how easily

your thigh fits in a hand, your chin in a mouth, your buttocks

in the crook of a hip how easy it is then to be filled.

This is real to you: this is what you turn sex into.

You feel your knees pushed open with thick warm thumbs and

you can feel your knees are skinned and then you see them

getting skinned, you see yourself somewhere beyond that shadow.

You see your white skates on the drive, the slope of the tar,

and into this vision you escape. Leave. Cease to exist.

You are gone from the place of the thin bed and the blue panties

wrapped around an ankle. Someone else has taken your place.

You then are on the driveway and your cat is in the flowerbed

and your mother looks out the kitchen window at you in your

good dress which you are not supposed to wear with skates.

You skate in circles and watch the sky, picking shapes

out of clouds turtle, clipper ship, heart, hand.

Your mother tells you Watch where you are going, young lady.

And even before you skin your knees you feel something

slowly rising in your throat, the way the cream lifts every time

from the milk in the glass bottles that arrive on Sundays,

no matter how many times your mother shakes it up for you.

It rises in you like that thick and lukewarm as your father’s skin.

The taste inches up but you keep skating, try to make the circles

perfect and small, try to smell the beefsteaks on the barbeque

in the side yard where your father calls over the fence

to the neighbor, saying This is the life. But when you hear

his voice it is enough to send you down. You fall.

Your knees are skinned and full of rocks but you’re almost

you again, panties wrapped around an ankle, undershirt pushed up.

You hear your breathing and his breathing. You’re hot.

Your eyes are open and staring at something they

don’t even see. And when finally it happens you realize

that it isn’t your father filling you this time, he is

only making you fall. It hits you that you’ve done it again:

this shrinking into someone, then somewhere else. It is always

the same. You cannot control it. You never learned to skate.

You are there in your grown up bed with your lover and you have

just made love and he says Isn’t sex amazing and you say Yes.

- Alice Anderson