Tom Goff reviews Entrekin’s work and her reading which highlighted her book Change (will do you good). Entrekin featured May 1, 2006 at the Sacramento Poetry Center/HQ for the Arts, 1719 25th St.

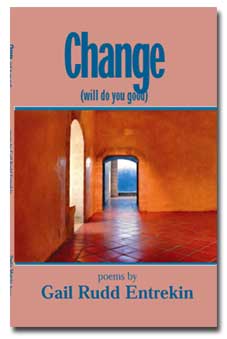

On Monday, May 1st, Rhony Bhopla was the Poetry Center’s gracious host for the Nevada City poet and Sierra College professor, Gail Rudd Entrekin, who read samplings of her newest work, as well as generous portions from her volume Change (will do you good), published in 2005 by Poetic Matrix Press. Following the Poetry Center link to Entrekin’s name will reveal that Entrekin writes knowledgeably, and with a rich vocabulary, about the natural world. But it was also good to attend the reading and hear the poet’s voice. She recites in a natural, conversational register, with a brisk yet always intelligible pacing. (In conversation afterwards, the poet mentioned how incongruous it is that Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gentle” should affect her at such an intimate level; and yet that Thomas should recite the poem, on record, with such a booming, actorish delivery.)

Altogether, Entrekin’s own delivery suggests the very ruse James Merrill detected in Elizabeth Bishop’s “lifelong impersonations of an ordinary woman.” Note, however: the important word is “impersonations.” Entrekin can write affectingly about family relationships and the complexities of feeling in which they enmesh us: she recited a poem of abashment at her own violent over-investment in her son’s school wrestling tournaments, complete with instant hatred towards the boy’s opponents. And, in keeping with her pose of ordinariness, Entrekin (with her own teenagers to provide material) can make like a soccer mom. But how many soccer moms can write—as in such items fromChange as “The Mothers Speak: What We Want”—poems that conclude as this one does?

We want to pause in the clarity of this bright day

and find our place, how each of us

is our own brave mother’s child, each a link to the children

who hold our hope in their familiar hands,

to stand together on this mountainside

and know we have the power

by adding one or two or three good humans to the pot

to change the world.

If these lines seem a bit too plainspoken, words such as “stand together on this mountainside” a bit too cozily axiomatic, look again: at the effective use of the modifiers “bright” and “brave,” alliterating with each other, not one adjective too many; at the use of “hope” in the singular, not the plural, connoting that there is but one hope, and that a slender one, carried as it is by children. Reflect also on the difficult act of collecting “children” and asking them to stand on a mountainside (I’m reminded somehow of the innocent cattle teetering slantwise on the hills of the Coast Range between Vacaville and Vallejo). And finally there’s the notion, Biblically resonant, that even the bravest humans are food for the pot, effecting change only as they themselves are changed.

Not all her poems are quite this simple in vocabulary or syntax; Entrekin employs other voices and gambits, some of them quite arresting in sophistication. If you’ve read Rilke’s famous “Spanish Dancer” (which finds a flamenco dancer striking an intensely hot match by force of gesture), now consider Entrekin’s “Spanish Dancer with Diabetes” (to the music of ‘Barcelona Nights’). Entrekin did not actually read this poem at the Center; but the fact that she did read one in a series of poems about her own diabetic daughter adds poignancy to the force and flair of such lines as these:

Spanish music; your clapping castanets,

I smell the sweet hay of your hair.

You circle past me in the kitchen

and I grab you quick, feel your bony ribs,

flat white belly, the heat of you,

the joy, flash in my hands.

One is left, moreover, to infer a mother at work helping a daughter through an actual “dancing” spell of dizziness, and recording it in a fashion that allows both to make light of the incident. Such delicacy of feeling also embroiders a poem Entrekin read expressly for her husband Charles, who was on hand (as were such regulars as Quinton Duval and B. L. Kennedy).

Altogether, I enjoyed the reading immensely. An engaging open mike followed. After Rhony herself provided a brief poetic vignette of her London days, Nora Laila Staklis read with energy from her chapbook,The River Speaks. Humor and insight punctuated Andy Jones’ and Brad Henderson’s readings from their joint effort, Split Stock. And Susan Bonta provided a poem written by her grandmother upon that lady’s ninety-ninth birthday; what a gift for her to have kept her wits and wisdoms so completely whole as in that poem, which jogs deceptively along—until the instant she describes her exact present viewpoint from confinement in bed: “My website is the ceiling.”

Tom Goff