Dan Bellm’s third book of poetry, Practice, came out from Sixteen Rivers Press in March 2008. His first, One Hand on the Wheel, launched the California Poetry Series from Roundhouse Press; his second, Buried Treasure, won the Poetry Society of America’s DiCastagnola Award and the Cleveland State University Poetry Center Prize. His work has appeared in Poetry, Ploughshares, Threepenny Review, Best American Spiritual Writing, and Word of Mouth: An Anthology of Gay American Poetry. He is also a widely published translator of poetry and fiction from Spanish. He lives in San Francisco.

Practice

Every seventh year you shall practice remission of debts.

Deuteronomy 15:1

How simple it ought to be, to practice compassion

on someone gone, even love him, long as he’s not

right there in front of me, for I turned to address him,

as I do, and saw that no one’s lived in that spot

for quite some time. O turner-away of prayer —

not much of a God, but he was never meant to be.

For the seventh time I light him a candle; an entire

evening and morning it burns; not a light to see

by, more a reminder of light, a remainder, in a glass

with a prayer on the label and a bar code from the store.

How can he go on? He can’t. Then let him pass

away; he gave what light he could. What more

will I claim, what debt of grace he doesn’t owe?

If I forgive him, he is free to go.

First evening prayer

It is possible

even in the darkness —

no, it is

more possible —

that is when your messenger

comes to me,

who has walked unappearing beside me

like starlight in the day,

angel that lives in the dust

of the earth, and knows

the distance of time, and the terrible

space between one human

and another,

that can hardly be crossed —

in the dark the messenger

cries, lift

your eyes up —

what I am dreaming I am seeing,

it is coming to be —

and climbs a coil, a rope,

a spinning ladder

that is the way

into day

in the night,

a place of God I didn’t know,

here at the foot of it,

the root of the tree,

not for me to ascend

but to pray to you in the dark,

that you have brought down

the infinite to me

when my head lay on a stone,

one earth wheeling

among the millions of your stars.

————————————————————————-

Terry Ehret is a poet and teacher, as well as one of the founders of Sixteen Rivers Press, a nonprofit, shared-work publishing collective representing poets of the San Francisco Bay Area watershed. She has published three collections: Lost Body (1993), Translations from the Human Language (2001), and most recently Lucky Break (2008). Literary awards include the National Poetry Series, the Commonwealth Club of California Book Award, and the Nimrod/ Hardman Pablo Neruda Poetry Prize. In 1997, as the writer-on-site at the Oakland Museum of California, she created a poetry audio tour for the Gallery of California Art; and from 2004-2006, she served as Sonoma County Poet Laureate. She has taught writing at San Francisco State and Sonoma State Universities, California College of the Arts, Santa Rosa Junior College, and with the California Poets in the Schools Program. She currently leads private workshops in Sonoma County, California, where she lives with her family.

Sample Poems from Lucky Break:

Lucky Break

A white marble wheel

has many uses: travel,

for example, or shaping clay;

a simple lathe but, like any tool,

needing balance. Else

the center, which is empty,

cannot hold, lets loose

its own purpose,

fragments flying untethered

from any force centripetal,

explodes its form, stone

wheeling, broken

into clavicle and pelvis,

petal and wing,

like disaster,

like the first creation:

joy and death spilling

from the cracked jar — ah!

the thing it isn’t and

ah! the thing it yet

might be.

What It’s About

with thanks to Allen Ginsberg

Spring is about standing in the dark under the darker eucalyptus

and feeling the future like an ache in the throat,

in the lungs like drowning,

like waiting in silence for the bombs to fall.

Bombs are about who’s lying and who’s counting, and counting

is about numbers we agree to. Agreeing

is about investing your money in the same things.

Money is about money and also about what you don’t have.

Not having is about pain and pain is about being broken each year,

being broken by promises by grace by the bursting

seed-pods of deceit

and telling ourselves we will heal or if we cannot

telling ourselves it’s our place to be stupid and broken.

Our place is about three cars in the driveway

and streetlights and sidewalks

and sidewalks are about what’s worth protecting.

Protection is about terror and destruction and inevitable suffering

and suffering is always

about birth, about stains and mystery

and mysteries are always about the silence

the aweful, chilling silence that fills the right now before

whatever is about to happen happens.

March 18, 2003

How Words Began

Crab: from Old German krabben, originally Greek graphein, “to write”

Some say it began with a crab

scuttling sideways and clickety across the rocks —

across glistening gray-black sand. And a man

standing on the rocks and following,

first with his eyes, then with his feet,

the marks indented and dimpling the wet

tongue of the shore. A man wanting much

to hold the sun still, to lock the

here and missing here and missing sea.

A man turned over and over by the ends

of feelings, the light fleeing and returning,

the deep-in-the-bones ache pulling the living

from the dead each spring. Just such a man, kneeling

in the black-gray graphite sand, traced

with his finger the memory

of crab, of ragged claws, of urgent

return to salt.

House and Universe

To mount too high or descend too low is allowed in the case of poets who bring earth and sky together.

The first walls are a great animal sleeping inside the sound of the heart. Sound of the rain. Breath.

The second walls are far, like what is near in a fever. So far away there is no sense of wall, only odors and voices, and the very smallness of the self.

The third walls take you back to the first. To sleep. To dreams. And these are the walls you eventually fall through. This is when you learn what your lungs are for and how alone you are inside your pain.

The fourth walls are everywhere, and you can move among them, listening to the talk of a green bird in a cage. Or you lie on your back and turn them upside down and spend the evening alone and calling. Inside these walls are the spaces that might be yours. One day you make a little version of the world on a scale you can lean above. You stand in the hall with the green bird in the cage beside you, opening and closing the gate you’ve made in this world, and this is when you begin to know who you are.

The fifth walls are full of ghosts. When you sleep inside these walls it is hard to know which world you are walking in. These walls are old, and they are where your dreams will come from for a long time. Inside these walls you carry an invisible thing you don’t yet know how to name, even when it greets you, resting its cold hand on your back as you climb the stairs. You don’t speak of it, but each time you come back inside these walls, it moves close to you.

Inside the sixth walls you take your books, turning over each page where the invisible thing you carried home from the ghosts takes on voices and shapes and tells you stories about yourself. These walls are old and high, and here you discover how small a woman is supposed to be, and how big your ghosts are. You begin to write back to them and all the empty space you find you can fill with what you want to say,

and saying makes around you the seventh walls. Words that pull the white peaks of the sky together, a roof the rain now beats down on, that the creek rises beside. House of wind. House of water. Sound of the heart. The rain.

Fears in Solitude

Coleridge, alone and afraid, wanted to

cry out. Instead he grew angry

at the way politicians juggled the name

of God. Instead he grew sick

of the owlet atheism hooting in the twilight.

Instead he took long walks in the country

with William and Dorothy, packed his books

and left England to take long walks in Germany

with Kant and Goethe. Everything hurt him.

Everything he loved turned away. In his sleep,

a wind was blowing, and it brushed the strings

of his fears. Waking, he moved among

the shadows of figures that shone bright

in those dreams. If there is a God, he thought,

we are His severed hands, playing

a brutal music He cannot stop,

and cannot help but hear.

————————————————————————-

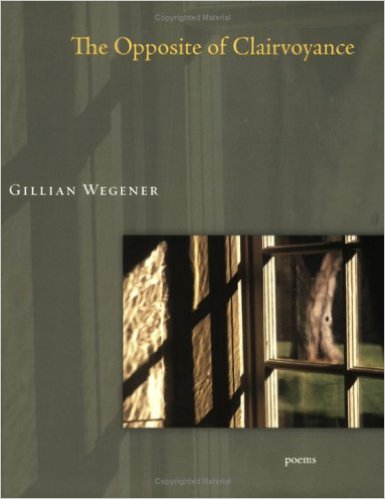

Gillian Wegener is the author of The Opposite of Clairvoyance, published by Sixteen Rivers Press in 2008. She’s had poems published in numerous journals, including Runes, English Journal, americas review, and In the Grove. A chapbook, Lifting One Foot, Lifting the Other was published by In the Grove Press in 2001, and she was awarded top prizes by the Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Foundation for 2006 and 2007. Wegener works as a junior high English teacher in California’s Central Valley. She lives with her husband and daughter in Modesto.

Reflection

So you have trouble shifting,

have trouble, are troubled,

you can’t quite manage how to make the leap,

even if it is not a leap really, but just a step,

or not even that, maybe a sitting up rather

than a lying down. Yes, if you have trouble

because you imagined her face so differently,

and now she is in front of you and her hair

is not even close to the fine perfection

you carried in your mind, not the auburn

you had pictured, and her eyes are misaligned

but so slightly it’s not worth mentioning. And

now she is in front of you, right here in front of you,

and you are married, and in the other room

of this house that you always thought would be

bigger and more rustic, in the other room, there is

a child whom you assumed would play the cello,

or at least the guitar, but mostly the kid

seems to stare out the window. The kid is a dreamer.

And that wasn’t the plan. And you go off to work

every day and stare at yourself staring back at yourself

in the train window and are surprised because,

boy-oh-boy, is it hard to make the shift between

all that you imagined (you were a dreamer) and

all that really is, and could that really be you…

the guy with the tie and the crow’s feet and the glasses

in which there is an even smaller reflection of you

staring back in disbelief.

Funderwoods

The woods are oaks and spread their woody fingers over us.

Paint peels on the aging signs, this one a toothy squirrel

holding up a paw: You must be this tall to ride alone.

The girl running the carousel is a madonna, that serene.

Tickets are 10 for 10 dollars and curl in the hand like a pet.

Music falls out of the smaller trees, splashes and evaporates.

You must be this tall to ride alone on the child-sized roller coaster,

the tilt-a-whirl, on mini airplanes, on dervishing tea cups hot to the touch.

The bumper cars are broken, heaped together in a junkyard pile, and

the painted eyes on the squirrel are the almost-blue of skim milk.

The boy running the roller coaster can’t stop looking at the carousel madonna

while her horses lift up and down, leather reins worn to brittle strips.

The airplanes have names like Thunderbird and Thundercloud and

there’s no waiting in line here. Two kids on that ride, one on this.

Under the roller coaster, weeds with feathery leaves bend and flower.

Music falls out of trees and into our laps, a little sticky, a little cool.

The rides click and whir, creak to stops, jolt to starts.

The oaks spread their woody fingers and pattern the pavement.

The roller coaster boy has left his post and whispers his plans

into the carousel girl’s benevolent ear. She smiles, still serene, and

takes the curled ticket of a child who runs to find the perfect horse,

who cannot imagine a more shining moment than this.