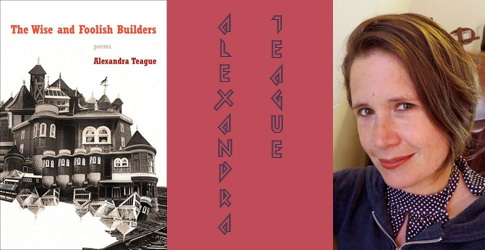

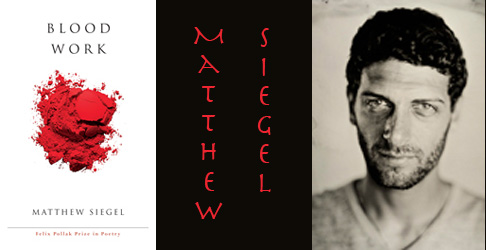

Alexandra Teague and Matthew Siegel

Monday, May 25 at 7:30 PM

SPC at 1719 25th Street

Host: Tim Kahl

Alexandra Teague is the author of Mortal Geography (Persea 2010), winner of the 2009 Lexi Rudnitsky Prize and 2010 California Book Award Gold Medal in Poetry, and The Wise and Foolish Builders (Persea, April 2015)—which revolves around the story of Sarah Winchester, Victorian heiress to the rifle fortune. The recipient of a Stegner Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and the 2014 Missouri Review Editors’ Prize, Alexandra has been published in journals including The Threepenny Review and The Southern Review. After years of teaching in the Bay Area of California, she is currently Assistant Professor of Poetry at University of Idaho.

Many a Goat

The imitative faculties of the. . .boy and his desire for glory

have been greatly stimulated by the coming of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Many a peaceful dog has been roped. . . by urchins whose imagination

converted him into a bucking bronco; many a goat has been mistaken

for a rampant buffalo and hunted over imaginary Rocky Mountains.

—Brooklyn Eagle, 1894

A rowdy teenager named René Secrétan, who liked to dress up

in a cowboy costume he’d bought after seeing Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show,

was probably the source of the gun.

—New York Times Book Review, Van Gogh—The Life, 2011

Even here in Auvers, the boys are not immune

to the West’s wild lure. They buy drinks

for Van Gogh—send their girlfriends to taunt

with false seductions. Pretty peasants,

innocent prostitutes: the imagination turns

cotton to silk, cornflower blue into the red-

striped candy of garters; farmyards into Hell-

on-Wheels towns that roll behind rail crews

like a dark flock of crows. Van Gogh understands

this: mountains spiring through cornstalks,

snow capping the summer fields: lead-white

in a swirl of sunflowers. Many a peaceful dog

would rather be a bronco. Many a boy,

a canvas. Broken sky. The meringue

of prairie schooners. The imaginary plains

where guns gleam, pistol-twirled stars above

cypress. Many a tree would rather be a church

steeple. Many a church steeple: fire’s scorch

and gutter through the thatches of men’s

hearts. Maybe it’s true he steals the pistol—

antique, likely to malfunction—holds it

angle-askew in the field: a brush to swathe

the wound of a body. Maybe it’s true

the boys aim it. Their Dutch-Indian enemy,

innocent, inebriated: Yellow Bonnet’s

war paint and canvas: lodge poles of madness

holding up his mind. They’ve seen it all

before: blood on stage, and Bill himself,

that scalp in his upraised fingers like a palette,

a sun-spot, a gold-glass bottle. Van Gogh

understands this. He is not the first man

for whom death is beautiful.

originally published in Conte

Matthew Siegel was a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University. His book Blood Work won the Felix Pollak Poetry Prize in poetry from the University of Wisconsin in 2015. He teaches literature and creative writing at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

The electric body

changes like a sky bleeding peach,

gray feathers and smoke –

– a body circular as the earth,

water and air,

rivers surging through.

*

Eight quarts

of blood

run laps inside

my body

arrive, leave

like a Psalm

the chorus

to an electric body-

song.

*

At sixteen something broke inside me

in the gym locker room. I’d never wear

those shorts again. Breath swept

from me;

mist pulled

from boiling water.

*

My body is a series of bodies:

now & before

I realize how much blood

moves within me.

I wear this living skin –

wear it in the sunlight,

in the forest, in the city –

wear it like a suit

of metal, a suit of gauze –

my face of abalone, of straw

assembling, trembling

apart in the water.

*

Dr. Green wore black vests,

had no skull. I could see the folds of his brain.

My mother told me how he kissed with his mouth

open. Waiting in my underpants

in his office I stole gauze pads, tape,

a plastic model of an inflamed colon

to show my mother how I felt inside.

It was hard to make her laugh back then.

His eyes, I really remember, sad like a horse’s eyes,

ringed with dark just the same.

*

Then came Dr. Chen who quietly examined the surface

of my tongue that day in his California office.

He laid me out on a table, touched my ankles,

wrists, neck with his starfish-hands.

At the bottom of his clear mug,

a bag of green tea bled into hot water.

He marked Chinese characters on a chart.

He told me even in English, I wouldn’t understand.

*

The first time I take the shot, I jab myself

in the side of the stomach, over an old wound

invisible to me. I shake a little as I pinch the skin

and wait for my body to finish sipping

from the thin needle. The doors to my body swing

open. Air rushes through the hallways

all the lights flickering on.

*

I want to make music

from what isn’t broken,

make memory disappear

like medicine absorbed

in the blood. I want to whittle a whistle

from my bones. Tenderize the sky.

Smear with my thumb

God’s purple night makeup.

Hello, hidden pain. So strange

how you resemble my old face.

Won’t you come inside?

originally published in The Rumpus