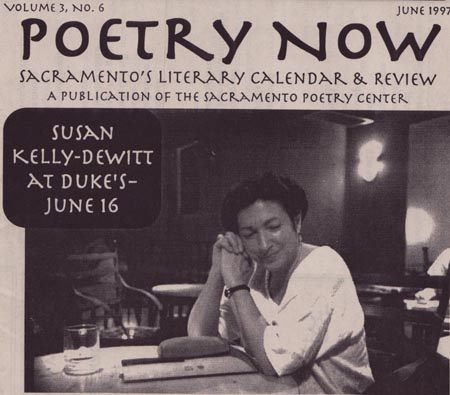

Susan Kelly-Dewitt

June 1997

Imagining Eugene Atget in Southside Park

So what if the universe is expanding

from a primordial dot? Like a god,

Atget drags

his heavy bellows

camera into the condensing

shadows, peels a thin

layer of soul

from a prostitute’s skin.

Fog drifts in—cools

the death rays that drip

through the shattered ozone—

then, dusk:

Ghost trees

congealing in a theater

of leaves . . .

Back home, sifting

through proofs, he will focus

on the shrinking,

the mortal jardins

imaginaires, on broken

pods of eucalyptus

and bits of oak

gall in the prostitute’s hair.

Think of him

as the face behind

the wind when the last

light glazes

the surface

of the lake’s smoked

lens.

On Turning the Same Age as My Father, When He Died

I could sift the burnt

rice fields all

night for his sad grains

fill a flask with his magic

soot, mix it

with whiskey and drink

his elixir

elixir of the short-timer

a potion for all those years

he didn’t live

happy or right.

Instead I sweep the night

sky clean, free

as the Swan’s

open wings. I breathe in

the concoction

of his dispersed atoms—

I inhale

deeply, his

diffused shine.

June 2001

Aesop Revised

The weather has turned warm—the cherry blossoms are out,

making me think of Aesop’s grasshopper and ant.

As a child my sympathies were entirely

with the unfortunate musician who could not help

fiddling day and night in the fragrant fields

since he was born with violin

legs and some twitchy gene that jiggled his nervous

neurons, instructing him to dance and sing, instead of laboring

to scrimp and save like the obsessive ant,

who was born with a banker’s heart. All summer long

the poor hopper lived only to please with a simple tune

while folks gathered around

his green-gold cloud of notes, and the ant filled his coffers

and plowed a straight line, to and from his storehouse

of stacked goods. Of course,

the cold winds came with the cutting of the grain

and the fiddler was left to survive or starve

all alone, a homeless beggar.

(Where were the crowds when minstrel dragged

himself to the ant’s locked door?) I still hate that

smug look on the dour ant’s mug

as he cracked open the door to the hopper’s faint

knock, reproved him, then slammed the door shut.

But here’s what Aesop could not know:

The sequel: That after hours after the ink dried

and he turned the page to the next moral tale,

the stingy ant reconsidered,

and welcomed the starving troubadour in, where he strummed

his tuneful thanks for free and filled the ant’s whole

house with the spirit of summer

while the snows howled all around them and the winter

moon rose, cold and white as a slice of frozen porridge.

Then they both slept—

the ant under quilts in his good bed, and the grasshopper curled

like a new green leaf beside the fire, where he dreamed

of cherry blossoms dusting his open wings.

March Catkins

When I stroke the blossoms’ furred backs

I understand the meaning of pussy willow . . .

until the silvered catkins arch

into flared suns,

fuzzy elliptical wicks

raining pollen light

into my burgeoning yard, my realm

of delight. Beware

the ides of March, the saying goes.

Maybe so—

yet today, the glory

of pussy willow shows

how much of pure radiance

this dangerous world knows.

May 2000

Painitng Class

Deborah is a bee this morning; she stings

her boy Luther with the hard, flat back

of her hand; she pounds the table

twice with the crossboned fist, flashes

a tattooed wrist knotted with inky

lassos. Nairobi’s not going

to have any of it. She pounds

the table back—harder—hurls

four-letter words like live bait.

She is boldly beautiful in a cobalt

pique sundress that bares

a puckered constellation of scars

across her arms and chest.

(Her face is untouched except

where the kerosene lit

a pink ragged moon onto one

shined cheek.) She’d like to peel

off the crosshatched lizard skin

and fold it away, permanently

creeased. Misty Lavender is mute

since her rape. She gets shaky

and afraid whenever Deborah

and Nairobi start to fight. Today

she crayons a purple scallop

of cloud in a choppy lemon

sky and dangles a neon zigzag

cord from it—a rescue

helicopter’s waxy rope

but no rescuer to slide down